Page 15 - Perspective Paper

P. 15

was able to evaporate from the affected areas, which would lead to an increasing rate of desertification.

The position of the Sinai Peninsula at the intersection between the Mediterranean, the Middle East and Africa

makes it noteworthy. Moist airmasses are formed above the Mediterranean sea, and at daybreak the heating

of the de-vegetated landscapes causes the airmasses to travel southwards across terrestrial surfaces. The

topography combined with thermal updrafts drive moist air high into the atmosphere. The absence of

vegetation means the condensation level cannot be reached and the moisture that could have formed low

reflecting clouds and local precipitation, now contribute to the greenhouse effect through absorption of

thermal radiation higher up in the atmosphere.

4.2 Regreening scenario

The Sinai having experienced several different states over geological time due to anthropogenic and non-

anthropogenic forces makes pinpointing the natural state and determining what constitutes sustainable

habitation challenging to assess (Wright, 2019). The Bardawil & Sinai Initiative and the intention of regreening

(and augmenting the biodiversity) of the region is not to subvert the arid ecosystem itself, but rather restore

its lost functionality as a ASAL and one where a wide range of plant taxa coexisted to form a fully biofunctional

ecosystem. Through large-scale revegetation and enhancement of aquatic life in Lake Bardawil and the

coastal zone, the Sinai Peninsula is expected to have noticeable effects on climatological conditions on a local

and continental scale. On a local level, across the Sinai Peninsula the expected effects include an increase in

humidity through plant evapotranspiration, and a subsequent increase in precipitation as a result of reduced

windspeed due to surface roughness and heightened soil moisture-vegetation-precipitation feedback.

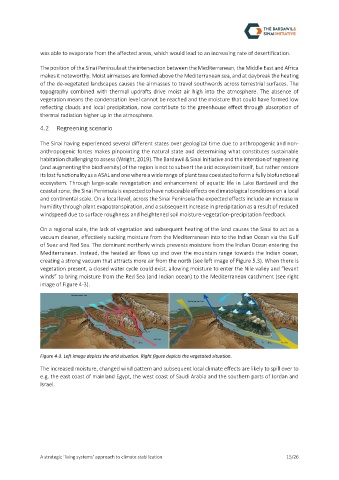

On a regional scale, the lack of vegetation and subsequent heating of the land causes the Sinai to act as a

vacuum cleaner, effectively sucking moisture from the Mediterranean into to the Indian Ocean via the Gulf

of Suez and Red Sea. The dominant northerly winds prevents moisture from the Indian Ocean entering the

Mediterranean. Instead, the heated air flows up and over the mountain range towards the Indian ocean,

creating a strong vacuum that attracts more air from the north (see left image of Figure 5.3). When there is

vegetation present, a closed water cycle could exist, allowing moisture to enter the Nile valley and “levant

winds” to bring moisture from the Red Sea (and Indian ocean) to the Mediterranean catchment (see right

image of Figure 4-3).

Figure 4-3. Left image depicts the arid situation. Right figure depicts the vegetated situation.

The increased moisture, changed wind pattern and subsequent local climate effects are likely to spill over to

e.g. the east coast of mainland Egypt, the west coast of Saudi Arabia and the southern parts of Jordan and

Israel.

A strategic ‘living systems’ approach to climate stabilization 15/26