Page 8 - Perspective Paper

P. 8

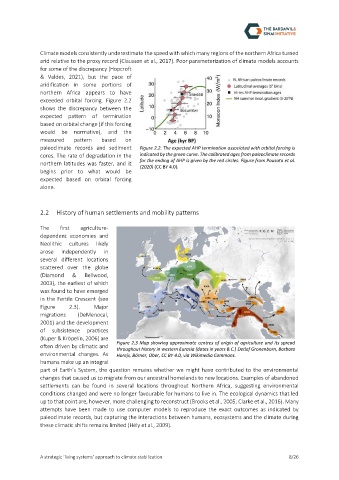

Climate models consistently underestimate the speed with which many regions of the northern Africa turned

arid relative to the proxy record (Claussen et al., 2017). Poor parameterization of climate models accounts

for some of the discrepancy (Hopcroft

& Valdes, 2021), but the pace of

aridification in some portions of

northern Africa appears to have

exceeded orbital forcing. Figure 2.2

shows the discrepancy between the

expected pattern of termination

based on orbital change (if this forcing

would be normative), and the

measured pattern based on

paleoclimate records and sediment Figure 2.2. The expected AHP termination associated with orbital forcing is

cores. The rate of degradation in the indicated by the green curve. The calibrated ages from paleoclimate records

for the ending of AHP is given by the red circles. Figure from Pausata et al.

northern latitudes was faster, and it

(2020) (CC BY 4.0).

begins prior to what would be

expected based on orbital forcing

alone.

2.2 History of human settlements and mobility patterns

The first agriculture-

dependent economies and

Neolithic cultures likely

arose independently in

several different locations

scattered over the globe

(Diamond & Bellwood,

2003), the earliest of which

was found to have emerged

in the Fertile Crescent (see

Figure 2.3). Major

migrations (DeMenocal,

2001) and the development

of subsistence practices

(Kuper & Kröpelin, 2006) are

Figure 2.3 Map showing approximate centres of origin of agriculture and its spread

often driven by climatic and

throughout history in western Eurasia (dates in years B.C.) Detlef Gronenborn, Barbara

environmental changes. As Horejs, Börner, Ober, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

humans make up an integral

part of Earth’s System, the question remains whether we might have contributed to the environmental

changes that caused us to migrate from our ancestral homelands to new locations. Examples of abandoned

settlements can be found in several locations throughout Northern Africa, suggesting environmental

conditions changed and were no longer favourable for humans to live in. The ecological dynamics that led

up to that point are, however, more challenging to reconstruct (Brooks et al., 2005; Clarke et al., 2016). Many

attempts have been made to use computer models to reproduce the exact outcomes as indicated by

paleoclimate records, but capturing the interactions between humans, ecosystems and the climate during

these climatic shifts remains limited (Hély et al., 2009).

A strategic ‘living systems’ approach to climate stabilization 8/26